- Home

- Fabio Scalini

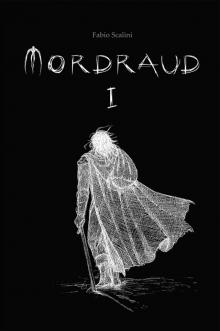

Mordraud, Book One Page 8

Mordraud, Book One Read online

Page 8

All the problems Varno was inflicting on their family. Eglade’s pain, and her feebleness. Even Gwern’s fits, which seized him in the middle of the night and had come close to killing him so many times. Mordraud had taken it upon himself to shoulder all this. Perhaps to show Dunwich how very little he actually did for them. But he hadn’t done it only out of spite. He was forced to by the times. To survive that collapse, striving to salvage what he could.

“That’s got nothing to do with it! If you can’t bear the idea that I live in Cambria, just come out and say it. Go on!” Dunwich burst out, irritated by his brother’s sardonic tone.

“Go back to your career, Dunwich. After all... like father, like son.”

Dunwich took the insult like a blow to the stomach. He turned ashen and looked away. His bottom lip quivered in anger. Mordraud got ready for the retaliation. He wanted to fight it out with him. He wanted his brother to attack and to thump him savagely, so he could have another reason to detest him.

“Don’t talk that way... please,” Eglade begged him. It pained her to helplessly watch that scene. A well-dressed young man and a scruffy boy with a ruthless stare talking like two adults pumped full of resentment.

“I’m not saying anything that’s not true, mum! He sends his money home, just like dad does! He’s never at home, just like dad. Then he visits, says goodbye and leaves again!”

“But he’s your brother, and you should be happy about his success...” Eglade murmured in difficulty. The cough broke up her words and forced her to slump onto the chair’s arm for a moment.

Mordraud pursed his lips so hard they disappeared.

“He’s not my brother.”

“DUNWICH!”

Gwern raced into the room, catching his foot on the table leg. He made a dive to hug his brother. The potatoes he was carrying scattered on the wooden floor, and Mordraud bent to pick them up in annoyance before they could roll out of reach.

“Hey, gently, otherwise you’ll crush me! You’ve grown so strong!” Dunwich cried. His face brightened. He seemed extremely glad of that boisterous interlude.

“You look like a true aristocrat! Have you got a sword too? And a gold walking stick? It is true everyone has a gold stick in Cambria?”

Dunwich bowed down to get a closer look at him. His appearance was still that of a toddler but he already spoke like a young man. His Aelian blood. Mordraud was staring at them, holding his breath. Wavering eyes drowned in the shadow of his gaze.

“You’re a good boy for your mummy and your brother, aren’t you? You’re a man of the house too now. Have you already learnt to read?”

“Of course I have! It’s easy. It is in Aelian too, and I enjoy it more. But I don’t have to do my practice exercises now as I’ve already done them today, haven’t I, mummy? So we can go and play. Will you come too?! We’re hunting squirrels. It’s brilliant fun. Mordraud’s expert at hounding them out. And then...”

Gwern was a river in full spate. Eglade weakly hoisted him from the chair and took him in her arms, rocking him with affection.

“A little genius, like all my sons. He practically taught himself to read.”

“Great, that’s really good!” commented Dunwich, nodding in approval. “Cambria’s always looking for gifted children who are eager to learn.”

Mordraud’s eyes narrowed and he gritted his teeth, but he said nothing. He didn’t want to startle Gwern, but he did have a couple of somewhat unpleasant things he’d like to say on the topic. It was already a miracle his brother hadn’t had one of his fits yet. Gwern had to endure a couple of brutal attacks daily: a mix of coughing, uncontrollable shakes and horrific retching so overpowering it felled him to the floor, making him drool.

“Do you really think I could come and study in the city too? Cambria’s huge, isn’t it? And are there palaces and villas, like Mordraud described?”

“Yes, enormous buildings...” Dunwich replied, his eyes on Mordraud. “But you’re still very young. Perhaps in future, when you and mum have recovered. And now I’ll let you in on a secret...”

“What is it? What is it?!”

“There’s a bag in my carriage, and inside the bag there are...”

Dunwich whispered the end of the sentence in the child’s ear. Gwern flew out of the kitchen without even touching the floor.

“Go now, Dunwich.”

“Please try and understand, Mordraud. I’ll speak to dad. I’ll convince him to stay home more...” Dunwich replied.

“You don’t even know what we’re talking about,” Mordraud repeated, in a wisp of a voice.

“Why? I thought the problem was that he’s never home... Is it more money you need?!”

“Leave, now!” Mordraud hissed again, indicating the way out.

Dunwich gave his mother a big hug and kissed her. He collected his cloak and his leather travel bag and headed towards the door.

“Come back and see me whenever you want,” Eglade whispered faintly. Dunwich nodded without uttering a word.

“SWEET BUNS! SWEET BUNS!” Gwern’s shouts of excitement reached the kitchen bouncing off the walls like bugle calls.

“THANKS, BIG BROTHER!”

***

Their family life had become irreversibly tarnished following Gwern’s birth. Varno was now over fifty and had lost most of his hair. He was dogged by aches and pains, and his body was a carpet of neglected scars. His reactions were no longer as swift and agile as they once were, but he went on fighting as a mercenary unperturbed, ignoring how his absence made Eglade suffer. It had become impossible for him to bear the slow decline eating away at him, day after day. He looked at the woman he’d loved and saw she hadn’t changed since that first day. He looked at his own image in the mirror. And merely observed an old man with one foot in the grave.

His fear became envy. His envy became hatred.

And, above all else, Varno began to hate Mordraud.

He was nothing like his father. He was shut up in himself, spoke little and showed affection for nobody but his mother and his little brother. He wasn’t as bright as Dunwich, nor as delicate as Gwern. He’d become the object of taunting from all the other children in the village, for no real reason. Nobody could stand him.

And he had those accursed green eyes. The same as Aris’s. His worst nightmare.

Varno began exploring murky thoughts about his wife. Why did none of his children look like him? Why were Mordraud’s eyes those of another Aelian? He’d never imagined he’d be able to reach such levels of paranoia, not when he was young and gave little thought to what the future might hold. But he’d reached them and had gone well beyond. He wasn’t even sure how far beyond.

Instead of trailing her in secret and tracking her movements as any jealous person might do, Varno threw himself deeper into escapism, moving further and further away. He knew his conjectures were unfounded, but he nonetheless needed an excuse to feel envious and to justify keeping his hatred alive. Rather than tackling the fear of time relentlessly passing, he desperately tried to flee from it.

Unsuccessfully.

Eglade had never recovered from the last birth. Initially it had merely seemed a long period of weakness, a lack of strength that forced her to bed for most of the day. But as the months passed, instead of mellowing, her condition progressively worsened. Her long liquid copper hair faded, her eyes dulled. Her mind played its tricks increasingly often, alternating delirious hallucinations with moments of clarity and chilling rationality. Days could go by without her managing to utter a word, or she would ramble on in her mother tongue, telling empty space about frozen forests, looming black skies and beings wandering in the gloom. Then, suddenly, she’d realise what was happening and would cry, on and on, endlessly.

Varno was never there during those moments.

Her husband had become a stranger to her. Varno existed merely in her memories: a young man full of vitality and energy, who’d enchanted her with stories of a world that had always been forbidden to her. She

could not fathom what had happened, could not make any sense of it. At first she’d hoped that, with the right dose of patience, everything would fall back into place on its own. That one day Varno would understand he couldn’t flee from the balance of time, which was generous to her and her children but merciless with him. The good moments became increasingly rare. But there was no improvement, not even the illusion of one.

She’d simply stopped reacting, no longer resisted.

Eglade was steadily slipping into madness, desperately nursed by Mordraud, who failed to understand what was happening. Varno never lifted a finger to help him, or her.

Yet he lifted his hands – a great deal – for other purposes. For hitting, for instance. Or to bring a glass of wine to his lips.

The situation grew incredibly difficult the year following Dunwich’s last visit. Each time Varno set foot in the house again, Mordraud became his target. When he couldn’t get his hands on the older boy, then he’d go after Gwern or, as a last resort, Eglade. His brother closed himself inside an impenetrable muteness, and his smile entirely vanished. The child’s merciless seizures grew ever more intense. Like an echo of his mother’s dark illness. Mordraud lived in dread that a single blow would be enough to kill him.

So he always made sure Varno found him, every time he had to.

He prompted him by insulting and jeering at him, until Varno turned his attentions away from the mother and Gwern and showered only him with his blows. Mordraud would usually get caught deliberately, but only after exhausting him with wearing chases and constant provocation. He wanted to be sure that once Varno had finished with him, he’d go straight to the village to drink. He was much less dangerous when drunk. He often forgot everything that had happened. Seldom did Gwern witness the whole scene, because Mordraud could smell trouble in the air, and before yet another episode could explode, he’d send his brother into the woods to collect the first thing that came to mind: blackberries, raspberries, mushrooms or simply sticks to burn on the fire.

“I’ll sort it out, mum!” Mordraud had said to Eglade one evening, after a particularly hard day, because Varno had remembered an old cudgel he’d hidden in the woodshed years before. “I know where he keeps his silver pieces. We’ll wait for a moonless night, take the lot and escape! You, me and Gwern... We have to!”

“Walking on a moonless night’s lovely,” Eglade had replied, in a dreamy voice, stretched out and motionless in her bed. Mordraud was helping her eat some watery soup he’d made, while Gwern toyed with the edge of the blanket in silence. Mordraud was worried about her, but above all about his brother. He looked like the shrunken shadow of his mother: the same ethereal and taut skin, the same vacant expression.

“Yes, it’s lovely. Want to come with us some time? For a... walk?”

“It’s lovely. But it’s also dangerous. Do you know what my father used to say, my darling? On a moonless night, the shadows behind your back are longer. He was always saying that. I’m not sure what he meant. My father scared me. I’m tired... I need to rest a bit. Varno will be back tomorrow with his basket full of fruits and cheeses. The ones Dunwich loves.”

Just hearing his brother’s name made Mordraud’s blood curdle in his veins. They still got the money he sent, but their relationship stopped there. He’d rather drown in the tide of punches and blows than ask his brother for help.

He’d have to run away with Gwern. A constant thought. But he couldn’t abandon his mother to her own end. Taking her away by force would be impossible. Eglade could no longer get out of bed. She couldn’t stand up. He wouldn’t even consider leaving alone: his brother wouldn’t last a day, and then it would be his mother’s turn.

All that remained was Varno’s work. Although it subsided day by day, following the gloomy decline of time, it was the only interlude of relative peace that Mordraud could still cling to.

But in the end, even that fragile island crumbled miserably.

During an unexpected campaign of attacks on an out-of-the-way and usually low-hazard front, Varno lost his right arm during a cavalry charge. After weeks of agonising pain and fever, he was packed off home with just a fistful of coins and a mountain of rage to work off. Mordraud was fifteen.

He’d believed his life couldn’t get any worse. He was drastically wrong.

Varno’s disgust of his family had now reached soaring heights. He was convinced he was holed up with foul aberrations of nature. Repulsive creatures waiting for nothing but his death so they could seize his money. His soul grew increasingly black. He moaned day and night, seated on a chair in the garden, ranting about how brave he’d been when his arm had been amputated. He made up stories where he took on an entire cavalry regiment alone. He behaved like an eternal convalescent, leaving even the slightest tasks to Mordraud.

When he wasn’t down in the village drinking.

The wine changed him into a wild beast powered by hatred and remorse that needed venting. His life was over, his work finished forever. Old age was eating away at him from inside. Starting from his mind.

On many occasions, he shooed away the doctors Dunwich sent from the capital for Eglade, costing his son huge sums and sizeable risk. He barred all contact between their home and the outside world. Even his sons weren’t allowed in their mother’s room; she lived endlessly confined and alone in the same dank dark room. In the end, he stopped feeding the Aelian in his folly, and prevented Mordraud from doing so too. He constantly monitored the larder and vegetable garden. He once savagely beat Gwern, after catching the boy while secretly trying to take Eglade a few wild berries.

The child came out of it battered and torn. He was bed-ridden for days, hovering between life and death, locked in his room and watched over day and night by his brother. They’d heard Varno go on yelling, smashing things and railing at them, flailing at the door ferociously. Mordraud had never been so frightened in all his life. And in his terror-oppressed mind, his blame acquired flesh, blood and a name.

Dunwich.

The brother who’d never saved them, who’d deserted them to lead a privileged life in the city that had slain his father. Cambria. That accursed Cambria. Because Varno had never actually come home from that battle. The armless man was a stranger.

Merely The Stranger.

His fear became envy. His envy became hatred.

A hatred so intense that it drove Mordraud beyond the hazy verge of despair.

***

“WHERE ARE YOU, YOU FOUL LITTLE CREATURE? YOU DISGUSTING FREAK?”

Mordraud had been smarter than usual. When his father returned from a whole day spent in the village, there would be clues and details that only he could pick up on. The trees’ foliage seemed to fall silent, the birds’ song changed and the few animals they still had in the courtyard would always scrape around in the dirt the same way. That way. That most feared sign.

Mordraud very quickly peered in through the bedroom window and saw Gwern was asleep on his bed. He still hadn’t recovered. He’d wake up from time to time asking for something to drink, then would slip straight back into his sickly oblivion. Mordraud unfailingly took the precaution of securing the bedroom door with a padlock he’d stolen down in the village, from inside a woodcutter’s shed.

His mother was the second stop in his ritual. Eglade was unconscious in bed, ever thinner and neglected. Her room was locked too, but he didn’t have the key to that one. A setback he’d managed to solve swiftly. The window was quite easy to open with a bent knitting needle, which he ran beneath a lose plank he’d unnailed with a hammer.

He had little time. The first cries could be heard at the end of the path.

The footsteps on the gravel grew clearer, the typical laboured rhythm of a man blind drunk. Mordraud darted into the woodshed, creeping behind a stack of old worm-eaten logs he had carefully arranged to create an inaccessible haven.

“You’re not worth the half of me without that arm of yours,” he hissed between his teeth, repeating the words as a sort of chant. “

You can’t reach me without that arm of yours.”

He pictured the stump. He found it nauseating. The Stranger would amuse himself by showing it to him, rubbing it on his cheeks until it drove him to throw up. Mordraud blocked the thought. He suffocated it while uttering his new special refrain.

“You’re not worth half of me...”

“LOCKED THE DOOR AGAIN, EH? WHERE ARE YOU, YOU REPULSIVE LITTLE LOUSE?!”

Mordraud felt the mayhem mount around him. The wood creaking, the lock juddering under The Stranger’s blows.

“THIS IS MY HOUSE. YOU WON’T LOCK MY DOORS!”

‘He’ll try round the back now, near the well. Then in the empty chicken coop. The old dog kennel next. And he’ll fall asleep in the living room,’ he thought mechanically, well-used to the series of grotesque steps in a ritual he’d learnt to perfection.

Mordraud remembered what had happened in each of those places. They’d been excellent hide-outs, but they hadn’t lasted long. The woodshed was the best of all: always to hand, ready and inviting was his father’s old blunt sword, plus a hard smooth club he himself had decorated with carvings during the weary long hours of escape in the woods.

“If he finds me, I’ll be able to defend myself this time. You’re not worth half of me... without that arm of yours...”

He’d trained to the point of disfiguring his arms, whenever he could, every day for months. His muscles were not yet ready to handle a blade, but the years hadn’t been spent in vain. Mordraud had hammered all the tree trunks in the forest, he’d snapped branches, lifted stones and dug trenches. His strength was not easy to perceive, concealed inside the puny body of a twelve-year-old. But his sinews were like cast-iron.

Tremendously heavy and terribly fragile.

“YOU’RE IN HERE, AREN’T YOU?!”

The Stranger had changed routine. No armchair, no kennel. The woodshed door flew off its hinges like a playing card, and Mordraud felt his heart plummet. An unbearable tremor prevented him from squeezing his left hand around the hilt. “You can’t reach me without that arm of yours,” he repeated to himself, eyes nearly closed. “You’re not worth half of me without that arm of yours.”

Mordraud, Book One

Mordraud, Book One